It is never to late to begin repair.

Sherri Clemons, Tribal Heritage Director, Wyandotte Nation

Our trip began with a flight from Tampa, where we are wintering with our daughter Louisa and her family, to Dallas/Fort Worth Airport on Wednesday, March 5th. From there we drove north to Edmond, Oklahoma, approximately 200 miles, where we stayed with relatives, Dian and Jim Sill. Their hospitality, interest in this work, and their deep, practical faith were a good place to begin a journey full of unknowns.

In order to be respectful of Tribal sovereignty, we sent letters to the Tribal Historic Preservation Officers for each of the thirteen Nations we were intending to visit, describing our plan and assuring them of our intention to do everything respectfully. Only two Tribes replied. We were able to follow up with one, but not the other. About 5 days after we returned from our trip, we received a phone call from an elder of the Iowa Tribe, who had only recently received our letter. We were delighted that she had reached out and look forward to communicating further with her.

From Edmond we took three day trips: to the land of the Iowa Nation, the Sac & Fox Nation, and to the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City.

Our day in the Iowa Nation, about 25 miles from Edmond, was like several more that would follow. We had imprecise information about the location of the short-lived day school that was established with financial assistance from New England Yearly Meeting. Taking the now “ghost town” of Fallis as our chief reference point, we headed north and east to a fork in a dirt road that was as close as we were likely to get to the site of the school. As became our pattern, we got out and walked around a little and then settled into worship in what seemed like the “right” place. In a simple ceremony, encouraged by a Wabanaki friend and teacher, our silent prayers were followed by offerings of tobacco and water. Our hope is that we could join with our “ancestors” and the ancestors of the children who attended the school in prayers for hope and healing. Time will tell.

Part of our preparation in the weeks leading up to our trip was to read sections of Modoc, Sac & Fox, and Quapaw student attendance lists that that Gordon and Suzanna Schell had collected at the Oklahoma Historical Society in February 2024. It was our way of remembering the central question in the boarding school research, “what have you done with the children”? and making the whole thing less abstract.

Our destination on Friday the 7th was more specific, the Cultural Center of the Sac & Fox Nation in Stroud, Oklahoma, some 50 miles north and east of Edmond. The Cultural Center is a relatively new building in a cluster of offices and health facilities. A circular gathering and display area is surrounded by various offices and meeting rooms. The museum was was mostly inaccessible, since the space was being used as a classroom for a ribbon-shirt-making workshop.

After an awkward beginning, we settled into what ended up being an hourlong conversation with the Center’s receptionist and guide. He had a lot to tell us about his own life and his experience as a Native person of Kickapoo, Meskwaki, and Ojibwa heritage. He shared very little about the boarding schools, having warned us that it was not something Indian People like to talk about with white people. He did tell us that his grandmother and two of her sisters were sent to Carlisle Indian Industrial School and that only his grandmother returned. The fate of the others remains unknown. “The damage has been done, and can’t be undone,” he told us. He also pointed us to the spot where the Sac & Fox Agency Boarding School was located less than a mile away.

Now the site of the Tribe’s water tower, we spent some time praying there and then went on to the the Sac & Fox cemetery, 5 minutes down the road. Two things stood out. Among the numerous graves structured in a conventional (to us) manner were a number that consisted of a low mound, perhaps two feet tall at the center, covered with small stones. We do not know the history or significance of this, but they were a reminder that we were on someone else’s terrain. We also found graves inscribed with many of the family names of students we had seen listed on school attendance records. What really caught our attention were the graves of two of students whose names we had read just a week or so before. (They died as adults.)

We spent Saturday touring the very impressive First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City and packing up for the next stage of our trip.

Early Sunday morning we left Edmond for Hominy and the Hominy Friends Meeting, about 110 miles northeast. Suzanna and Gordon had met the Hominy pastor, David Nagle, in 2024, and Mary and Gordon had corresponded with him. David invited us to join them for worship and their monthly potluck lunch afterwards. The service was, as expected, very evangelical compared to many New England meetings. Several of the hymns were familiar, including the George Fox Song many New England kids sing in First Day School and Junior Yearly Meeting. The Meeting was established at the request of Osage elders in 1904 and the congregation is largely Osage. Most unusual was the singing of “Happy Birthday” and the final hymn, and the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer in the Osage language.

Lunch and conversation with several members of the meeting was very enjoyable. Later that afternoon we drove through Skiatook, site of the Skiatook/Hillside School, and arrived in Miami in time for dinner.

We drove north on Monday morning to see the territory of the Quapaw Nation and the Superfund site that includes the now-abandoned towns of Picher, Treece, Douthat, and Cardin.

The Quapaw were among the first tribes to be removed to Indian Territory in the 1830s. We were welcomed to the Quapaw Tribal Museum, which featured a large timeline and a climate-controlled room where they display a variety of cultural items and photographs. The guide did not seem aware of Quakers’ role in the Agency school there and it did not seem our place to correct her. From there we went looking for the site of the Quapaw Agency Boarding School and the Tribe’s cemetery. We did not have precise information and were not able to locate them. We did visit the Tribe’s powwow grounds where they have been gathering for every July for 150 years. Besides the permanent seating and drum arbor, there were 20 or 30 family arbors arranged around the main circle. Simple structures with open sides provide shade (we were warned that it could easily reach 108° in the summer) and a place for families to gather during the festivities.

Before heading for the Miami powwow grounds, we took the time to drive north on US 69 through the ghost towns of Picher, Cardin, Douthat, and Treece (Kansas). The site of an early 20th century lead and zinc rush, unrestricted mining, and mountains of highly toxic mine waste, these towns tell a story very much like that of the Osage People. Highly valuable mineral resources were discovered and mining companies rushed to secure leases and plunge into underground mining. Unscrupulous “guardians” and public officials cheated the Quapaw People out of their land and the enormous wealth being created. A brief period of extravagant prosperity was followed by fraud and exploitation that left the Quapaw with little but enormous piles of “chat”—mine tailings full of toxic heavy metals that leached into the ground water and rendered the towns unsafe for human occupation. The EPA declared the towns beyond reclamation and ordered the residents to leave. Unwilling to surrender any of their land, for the last three decades the Quapaw Nation has been engaged in efforts to do what the federal government would not, reclaim the land for agriculture.

After that side trip, we headed west to see the Miami Nation’s powwow grounds, hoping to locate their cemetery and the site of the Miami day school that was operated by Friends from 1876 to 1893. A short visit to the powwow pavillion and an offering of prayers, tobacco, and water were all we were able to do. Most of the Miami had been removed to Oklahoma from ancestral lands in the Ohio River Valley.

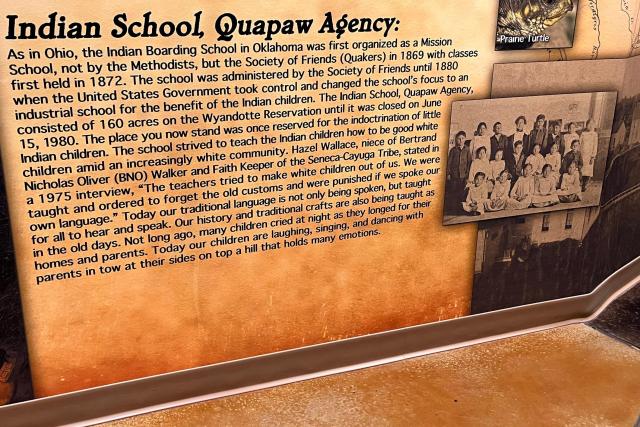

Wyandotte, occupying the southern half of Ottawa County, was our destination Tuesday. The town is the location of Tribal government of the Wyandotte Nation (moved from the upper Great Lakes region). It was the site of the Seneca School, also known as the Seneca, Shawnee and Wyandotte Indian School, and is now the location of the Tribe’s Cultural Center.

The Seneca School was established by Quakers in 1871, became a government industrial boarding school in 1880, and continued to operate for the next 100 years. The land was returned to the Tribe in 1980. A timeline of the Tribe’s long history covers the wall that circles a central meeting area. The section below describes the school and how some members of the Tribe remembered it.

Staff at the Cultural Center were very welcoming and kept checking in with us as we walked through the exhibits, asking if we had any questions. Anxious after our earlier awkward encounter at the Sac & Fox Center, I tentatively raised the question of the boarding schools and in particular asked if they were collecting lists of students from the Seneca School. Beci Wright, the Tribe’s Cultural Researcher, said they were indeed collecting lists and was very interested in what Suzanna and Gordon had collected in March 2024. We moved to her office and I was able to transfer a number of scanned index cards listing students and basic information about them. A lengthy conversation followed about the work they were doing and ways we might be helpful. At one point, Beci turned and pulled two letters off a stack. One was Rebecca Leuchak’s letter as Presiding Clerk introducing the Yearly Meeting’s report to the Department of the Interior. The other was the letter we had sent in February. “Now this makes sense,” she said. Outreach by letter was important; showing up let Beci know we were serious.

Wednesday (the 12th), we met with Syd Colombe (Modoc), Tribal Cultural Preservation Officer for the Modoc Nation, and Rachael Blackstone (Cherokee), the Tribe’s curatorial and research associate. Gordon has been in contact with Syd since March 2024, has shared student lists from the National Archives repository at the Oklahoma Historical Society, and tried to help sort out the lineage of a young Modoc girl adopted by a missionary family. Our meeting with them was the one confirmed appointment of the trip.

Syd and Rachael greeted us warmly and showed us around their archives and several exhibits of Modoc cultural objects that had been donated, loaned, or, in a few cases, purchased on EBay. In all, we spent about 4 hours with them, including a tour of the 19th century meetinghouse still standing and a slow, reflective walk through the Tribal cemetery next door. Syd pointed out the graves of her family and of one of the only young men to survive the 1873 massacre and removal.

They also pointed out a new grave, one that had not been there when Suzanna and Gordon visited in March 2024. It was the burial site of a teenage Modoc boy who had died while attending Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. It was noteworthy since Gordon had come across correspondence between the Indian Agent and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in which the Commissioner expressed sympathy but declined to arrange for the return of the boy’s body to his family, citing their past practice. We were glad to see that had finally been corrected.

Our conversations with Syd and Rachael were wide-ranging including family histories, the complexities of language reclamation, research sources and contacts, differing opinions about the rematriation of human remains, contacts (and politics) between the Modoc in Oklahoma and those who remain in Oregon, and the story of Frank Modoc. He was recorded as a Friends minister and died in Maine while trying to advance his education at the Oak Grove Seminary in Vassalboro. We parted with promises of our return and the intention to find ways that our Yearly Meeting can support the restorative work that they are doing. On our way back out, we passed one of the five herds of bison the Tribe has been raising.

Our last three days, based in Shawnee, were a little anticlimactic after the rich encounters we had with Wyandotte and Modoc Nations. Thursday we spent visiting a series of cemeteries and overgrown fields looking for the sites of schools and missions established with the support of New England Friends for the Absentee Shawnee and Citizen Potawatomi.

The Absentee Shawnee, led by Big Jim, were a particularly conservative band, resistant to the religion, education, and agricultural practices being urged on them by the missionaries and Agents. It is not clear how John Mardock convinced them to send their children to the school that was eventually built there.

The Citizen Potawatomi were eager for the education offered. They had accepted the bargain of U.S. citizenship and allotment in exchange for relinquishing their land and treaty claims, but were deeply disappointed when the government failed to protect them from the schemes and predation of land-hungry white settlers. They moved to Indian Territory in frustration but have since developed numerous services and enterprises that have made them the largest employer and a significant economic presence in the area. Their large cultural center in Shawnee tells the story of the Potawatomi People and their diverse attempts to make durable arrangements that would preserve the Nation’s sovereignty and culture.

The Shawnee Meetinghouse built by Friends in the early 1880s is located just south of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Center. We were able to see the worship space by looking through the windows.

We cannot say for certain that we found any of sites we were looking for, but we got as close as we could and offered prayers, tobacco, and water as we remembered the children who had gone to those schools.

We attended worship at the Kickapoo Friends Center in McLoud on our last morning in Oklahoma. The mission and school there were established by Elizabeth Test, a Friend from Indiana, with funding from New England Yearly Meeting. The house she built still stands and is used as the residence for the longstanding pastors there, Brad and Christine Wood. We had written to them in February but had not received a reply, so we were unsure of our welcome. After some initial hesitation, Brad welcomed us and showed us to the church where a congregation of about 18 gathered for worship.

There was a lot of singing. We recognized a few of the songs and did our best with the others. Christine Wood’s enthusiastic and ornamented piano playing reminded us of Jan Hoffman’s occasional turns at the piano. The service included many of the elements and forms Gordon remembered from his youth—responsive readings, readings from the Bible, a sermon. The brief period of open worship midway through the service seemed deep and centered. Several spoke about recent struggles and hopes. Afterward, cordial greetings were exchanged between attenders.

Brad’s sermon was based on John 3.16: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” (KJV) Apparently many of the area churches had agreed to observe the date March 16 (3/16) by suspending their normal homiletic plans to preach on the text.

Most of the attenders left promptly after the benediction. We had been forewarned that the Kickapoo were a very private people. We had further conversation with Brad who shared with us a slide show on the history of the Center and then took us to see the older church building, now a multipurpose space, the large arbor where they can hold outdoor services and meals, and the well-equipped kitchen in an adjoining building.

From there we headed south to Fort Worth and our flight home the next day.

This was a wonderful trip full of new landscapes and provocative experiences. Three reflections have continued to challenge us.

1. The schools established and operated by Quakers under Grant’s "peace policy" were important proving grounds for the elements of an assimilationist education. Links between students and their families, cultures, Tribes, and land were stretched or severed. Native languages were suppressed and the physical reminders of home—mocassins, buckskins, blankets—were all thrown away or burned (or kept by teachers and missionaries as souvenirs of a ‘dying’ race). But these early schools were small and local and the privations involved paled in comparison to the harsh regimen of the large, off-reservation Indian industrial schools operated by the government or by other religious denominations on contract. The enduring influence of Friends is most clearly seen in their vigorous advocacy for the complete erasure of Tribal life and identities and the wide-scale theft of Native land.

It is essential for Quakers to account for their conduct of the schools if we are to humbly and candidly engage with the descendants of those who attended places like the Seneca School and the Sac & Fox Agency boarding school and make good faith offers of reparative action. But it not enough. We must understand and be accountable for our embrace of what today have been judged genocidal policies and our willingness to employ coercive practices despite our own history of “sufferings” at the hands of the State.

2. Indigenous People tell us that for them the path of healing and repair is long and difficult. Friends can help through an honest reckoning of our past and our role in assimilationist policies and practices and through sharing our resources: archival, financial, and spiritual. We can make this journey with them, but, as Alaskan Friends have reminded us, Native People are driving and we are in the backseat. Giving up our need for control and for recognition is the only way forward.

3. Talk of reparations is often reduced to writing checks and sounds like a transaction. Our experiences and the wisdom of Patti Krawec (author of Beloved Kin) encouraged us to think about the importance of rooting reparative action in ongoing relationships. The course of repair between the Alaskan Friends Conference and Native Alaskans and between Quakers in Maine and their Penobscot and Passamaquoddy neighbors show how the work of repair is grounded in carefully nurtured, candid, respectful relationships.

Thank you again for your prayers and support. We feel privileged to have made this trip and hope fervently that it will help to begin to renew the relationship between the Friends of New England Yearly Meeting and the Quapaw, Ottawa, Peoria, Miami, Modoc, Eastern Shawnee, Wyandotte, Seneca-Cayuga, Iowa, Sac & Fox, Kickapoo, Absentee Shawnee, and Citizen Potawatomi Peoples.

To further this process, we intend to return next year as way opens and would like to bring others with us.

We further hope that rediscovering the kinship that binds us will lead to candid, respectful, and mutual conversations and to healing and repair.

Click here for a PDF version of this report, which includes photographs.

Note: Gordon and Mary's trip was funded in part by a grant from the Yearly Meeting Legacy Gift Fund.