Starksboro, Vermont, and Pleasant Prairie

Sometime around 1881, Mary Grinnell was appointed teacher for the day school at Pleasant Prairie, one of three schools in the vicinity for children of the Citizen Potawatomi. She had been teaching at the mission boarding school in Shawnee, Oklahoma. The Tribe had been settled in the area for nearly a decade and had been eager to have their children educated. The Indian Agent, a Quaker from Iowa, had been able to secure funds to build a stone schoolhouse in 1875, but a lack of regular funding for salaries and inconsistent attendance had made sustaining a school very difficult.

The Citizen Potawatomi Nation came to Indian Territory in 1873 “by choice.” Having been forcibly removed three times, from Wisconsin to Indiana to Kansas, Potawatomi elders believed the Indian Agents and Commissioners from Washington who promised U.S. citizenship and title to their own farms in exchange for relinquishing their tribal membership and the rights and annuities they had been guaranteed by their treaties with the U. S. government. People were weary of the moves and the instability. Too many had died along the way. Their elders thought this would be there best chance for survival. Their faith was misplaced and after years of difficult harvests and unrelenting encroachments by their White neighbors without any meaningful assistance from the government, leaders insisted they be given new land in Indian Territory.

It is unclear how the Potawatomi elders persuaded officials in the Indian Commissioner’s office, but in 1872 elders were shown land between the Canadian River and its North Fork that would become the new home of the Citizen Potawatomi. (It would take several years to work out competing claims, since the same land had also been promised to the Absentee Shawnee bands.)

Mary was from Starksboro, Vermont, and had moved with her restless Quaker minister father, Jeremiah Grinnell, to Ohio, Indiana, and Tennessee. Mary and her sister Eliza may have taught at the Freedmen’s Normal school in Maryville, Tennessee. Eliza married Friend’s minister Franklin Elliot and went with him to Shawneetown (Oklahoma) where Quakers operated a boarding school for the Absentee Shawnee, funded to a great extent by NEYM.

Mary appears to have followed her sister to Indian Territory. (Their brother Fordyce became a physician at the Cheyenne and Arapaho Agency and the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.) She taught at the Pleasant Prairie school for two years. In 1881, she married Thomas Wildcat Alford, a grandson of the Shawnee chief Tecumseh and a graduate of the Shawneetown School and the Hampton Institute in Virginia. Thomas taught for a while at Shawneetown, took over the Pleasant Prairie School when they married, and returned as head teacher to the Shawneetown boarding school. Mary and Thomas had three children. She died in 1892.

Thomas continued to teach in the Indian schools until the territorial government took over responsibility for primary and secondary schools and dismissed all the Indigenous teachers. He would serve the Tribe in many capacities over the years, fulfilling his father's intentions that he would one day be a leader among the Shawnee.

Here is a biography of Thomas Wildcat Alford https://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc2017416/ and his memoir https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000287192

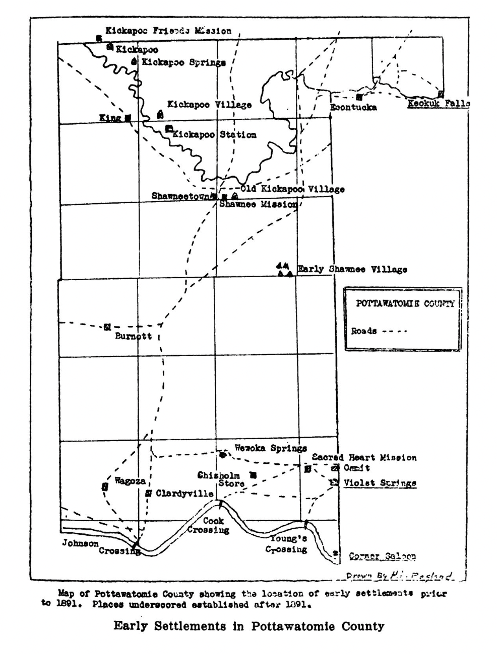

For Hobart Ragland's 1952 article and map of Potawatomi Day Schools see https://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc2123466/